Cantabrians should consider themselves officially in the gravy with this rare opportunity to enjoy a one-off screening of Pickpocket, from the curmudgeonly director who liked to refer to theatre as a “bastard art”.

My personal introduction to the cinema of Robert Bresson was akin to a miraculous forest fire in my brain as I hadn’t previously been privy to the fact that a work of art could exist in such a pure form. To many, Pickpocket is considered the teacher’s pet in Bresson’s classroom of perversely gifted children, with only Au hasard Balthazar coming in at a close second. While all thirteen of his feature films embody a level of cinematic perfection that any farsighted director would sell their pancreas for, Pickpocket retains an unprecedented position, spawning many a torrid accolade, such as that of the title character having inspired the brooding naivety of perhaps cinema’s most beloved psychopath in Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle.

With decades of unnaturally obsessive film scrutiny under my belt, and even though Pickpocket was released in 1959, I still regard Bresson’s alien aesthetics as the most futuristic thing on offer due to the fact that he truly reinvented the wheel in his quest to radically re-systematise the syntax of the cinematograph. In the director’s crucial Notes on the Cinematograph, he explains his rigorous use of both non-professional actors (whom he refers to as models) and parametric narration in which style is of equal importance to plot.

Many non-Bressonians may have deemed Pickpocket a snooze-fest but the denial of theatricality he achieves through an astringent regime of Brechtian alienation tactics is entirely intentional. By force feeding the viewer a disputatious diet of insipid imagery and dull dialogue, Bresson sets us up for an even loftier payoff when the film abruptly concludes to the perverted blasts of Jean-Baptiste Lully and presents us with one of the many transcendental moments he is notorious for. Authenticity was of great importance to Bresson and the film was actually banned in Finland due to its depiction of such convincing pick-pocketing techniques.

Bresson started out as a painter and his love for the figurative is evident here in his preference for focusing on hands (often at the expense of the face) which take on a near mystical quality due to the balletic abstractions they gracefully execute. Pickpocket is perhaps the quintessential spiritual crime flick for jaded existentialists, with its Dostoyevskian antagonistic relationship between central character Michel and a po faced police inspector, also its nail-biting suspense, which is said to have influenced Christopher Nolan’s grandiloquent war drama Dunkirk. Bresson’s characters are never black and white, as the director himself attested to in one of his canonical belittlements of the craft of acting: “We are complex. What the actor projects is not”.

DETAILS

Robert Bresson, Pickpocket, 1959

Sreened by the Canterbury Film Society

15 August at the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

See: https://www.canterburyfilmsociety.org.nz/join

IMAGE

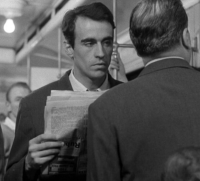

- Martin LaSalle (1935 – 1987), leading actor in his first film role in Pickpocket as Michel