Undoubtedly Bill Hammond was one of New Zealand’s greatest painters. Not merely in the trivial sense of the large sums his work went for at auction, but in terms of what he said about us as people.

Bill was the supreme dissector of the Kiwi (admittedly predominantly Pākehā). His works from the 1980s were surrealist visions of an uptight, upright, blue collar Christchurch suburbia. But bones and stone axes lurked among the macrame plant-holders and antimacassars. Visible beneath the skin of James K. Baxter’s “Calvary Street” lay half-beast Flintstones waiting to erupt. The wallpaper gave way into the darkness visible of rock-n-roll underworlds full of fantastic muso-monsters.

Bill’s passion for music may well have exceeded his passion for painting. A drummer of no small ability, the titles were often musical. Strange beings in his paintings, that seemed to have escaped from album covers, played phantasmagorical musical instruments. The really obvious art-historical comparison is Hieronymus Bosch’s depiction of Hell in his Garden of Earthly Delights triptych (c.1510) as a place of musical instruments of torture. In 1991, Bill’s work was included in a group show as part of New Zealand pavilion at the Seville World Expo, enabling the artist to see Bosch’s handiwork in the flesh at the Prado in Madrid.

Bill was inventing a kind of postmodern history painting out of pop art without even realising it. The traditional landscape was there, though often transformed as something sitting on a table. The deference to England was more or less in the bin and post-war America was the centre of the cultural world. Comic books and album art became resources. Bill responded in a way no one else was really doing in New Zealand as fine art, but you do see it in things like Fane Flaws’ graphics for the opening credits of Radio With Pictures and the art pop aesthetic of Split Enz.

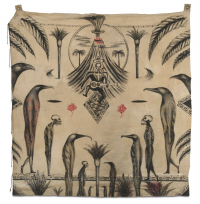

In 1989 Bill went on a tour of the Sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands with the Department of Conservation and the Royal NZ Navy and was profoundly struck by rocky promontories largely untouched by humans, where birds were the dominant creatures. In combination with a visit to Japan in the early 1990s and his introduction of the flat, linear, Japanese graphic style, this resulted in a paradigm shift – the bird paintings with their ecological and colonial themes. Bill hated being asked to explain what it all meant and would tell people to work it out for themselves. Ave, Bill. Ave atque vale.

IMAGE

- Bill Hammond, Radio On, 1985, collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū; presented by the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council, Wellington, 1990

- Bill Hammond, Volcano Flag, 1994, collection of the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū